Unintentional Design: Procedural Generation & Soulless Games

Contentification has changed the way games are made for the worse.

I’ve never really rolled on randomization tables.

I started playing TTRPGs with a d6 and a hand-drawn map, no rule book in sight. Every element of the story was fabricated on the spot by the players and GM creating the fiction as we played. When I was introduced to D&D 3.5, I was enamored with the tomes of creatures to fill a fantasy world and the mechanics I could exploit as a player to have a unique character in the stories. Those were tools that, as a player and GM, I could use to help myself as a creative craft the experience I wanted to have.

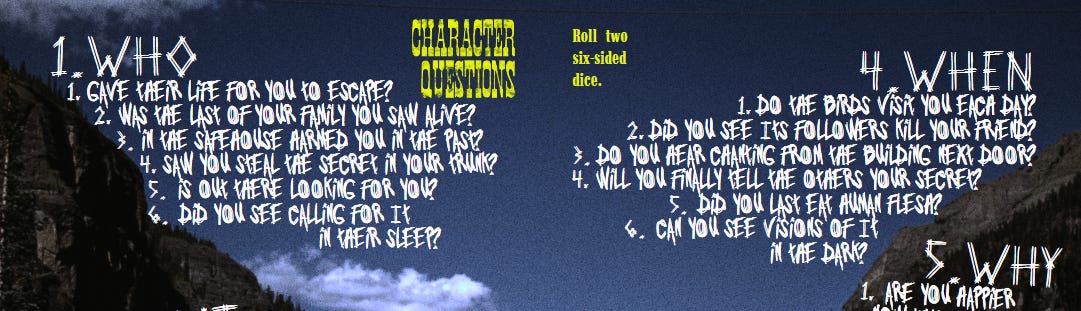

The books for many TTRPGs are also full of tables for all manner of things. Roll 1d100 for loot. Roll 1d20 for monsters on the road. Roll 1d6 for a character quirk.

I like these tables for the same reason I like the Monster Manual: it provides a huge list of options that I can pick and choose from to add elements to the story with intent. Rolling on a random table instead of choosing something from it that fit the fiction at the time was something I initially didn’t like because it created story elements without any story around them.

Okay, I rolled. But why are there wolves on the road attacking the party? Why do the goblins have a magic ring to be looted? Teenage Eric would rather have just decided what made sense at the moment and had it happen rather than leaving it up to chance. That was my experience from the “d6 and a map” games we played in middle school and there didn’t seem like a good reason it couldn’t work for the games with 3 books.

Since my youth, I’ve come to appreciate these tables more. These results on a table create prompts for us as players to fill in with answers that can create a compelling narrative, which is great when the purpose of the game is improvisational storytelling like in most TTRPGs. My own game, The Last Hand, uses random tables to help players who might get stumped coming up with something on their own.

I think it’s a great tool for these kinds of tabletop games.

However, I’ve noticed a trend of randomization in other games that doesn’t give the same freedom to the players to craft a story from these elements: video games.

Using procedural generation to create the world for your players is a great way to add replayability without having to hand-make hundreds or thousands of environments, but only if the narrative exploration or environmental storytelling aren’t core to the experience.

Today I want to discuss how procedural generation impacts the player experience in narrative video games, examples of it being used to great effect or ending in disaster, and comparing some games with many similarities apart from the environment being handcrafted or randomized.

I like to explore worlds full of things to discover.

Like many people my age, some of my first experiences with big open-world video games are from Bethesda’s Elder Scrolls games like Morrowind and Oblivion. When they released Fallout 3, it became one of my favorite settings and I fell in love with the franchise.

These games were full of hand-crafted locations and interweaving questlines that told interesting stories about the people that inhabited the world. Even without dialogue or NPCs, you could stumble across caves or ruins that had notes or even just items that implied what happened there, like a burned down house with a “Summon Fire Elemental” scroll within it, or a skeleton in a bombed out ruin’s bathtub alongside a toaster. These hand-crafted environments tell stories as you wander and explore without being tied directly to the game’s quests, making you feel so much more immersed in the world.

Are we happy?

Recently I started playing a game called We Happy Few. I’m a bit late, I admit, as it was available in early access in 2016 and had a full release 2 years later after significant overhauls to the core experience. It also wasn’t exactly heralded as a phenomenal 10/10 experience and had its fair share of criticism when it released. It does, however, make the flaws of randomization so apparent. It is exhausting to get to the experience that I desperately want to be an enjoyable one.

We Happy Few has a very compelling setting and story. You begin playing as Arthur, a man with a job censoring newspaper entries from the past in a version of 1960s England where citizens are compelled to take a widely available drug called Joy that makes everything feel great. You quickly see past the curtains in this dystopian society as Arthur gets kicked out of his job and cast out as a “Downer” who doesn’t take his Joy, beginning a journey to remember his past and track down his brother Percy who was taken away with the other young children by the Germans many years ago.

Early in its development during its early access release, We Happy Few was more of an open world survival craft game where a player would die and have to restart and you were struggling to survive in this world that doesn’t care for you. Because of this, it used procedural generation to build a different world each time you played. As it developed, it took on more of a story-driven format becoming the game that it is now. It keeps the need to eat, drink, and sleep but makes the consequences less lethal. It lets you save your game and pick up where you left off when you die. It is now a typical adventure game in many ways.

What it kept from that first iteration, however, was the procedurally generated world. The environment, from fields to forests to city streets, is all randomly cobbled together from a pool of the game’s assets. There are handmade locations, complete with self-contained questlines, in that pool that will pop up in the appropriate environment types (you won’t find a cave in the middle of a town for example), but the space between all of these points of interest is randomized and their location in relation to each other is as well.

What can happen (and did for me) is massive expanses of absolutely nothing interesting between points you need to visit for quests. I had to spend close to 5 minutes just walking along a path with nothing of note apart from some empty ruins to get to a quest marker, only to pick up an item and walk back to return it to the NPC who wanted it. 10 minutes of walking through an environment with nothing to say, nothing to look at but the trees and bushes randomly scattered across the ground, and no story to tell me apart from the person who wanted the engine to a destroyed car.

What I’m getting at is that this is clearly not the intended experience by the designers of We Happy Few. There could have been many other little stories and quests along that path, or the car could have been closer to the person who wanted the car engine.

I could have enjoyed that 10 minutes, or turned it into hours of exploring their world like I have enjoyed from Bethesda’s older titles. Instead, the randomization came out a different way. There was no intent behind the experience I had. It was just a computer tossing elements of an environment to fill space between the story the creators were trying to tell. It was generating content rather than artfully craft an experience.

I don’t want to just rag on We Happy Few, as the designers have acknowledged this shortcoming and wish they hadn’t kept with it because it “doesn’t make any sense.” I hope that the lessons that Compulsion Games learned here can be carried over to their upcoming title South of Midnight, because it’s clear that they have talented storytellers and interesting worlds to explore.

Intent is important.

What We Happy Few struggled with was intentionally designed space. They couldn’t curate the player’s experience between their points of interest, having to rely on their procedural generation algorithm to create a space that is good enough. This works in games like Minecraft or Don’t Starve, where the game doesn’t direct you and you are free to dictate your own experience, building your own bases each time you play with the expectation that you will play over and over and over again exploring new worlds each time you do.

Much like the random tables in TTRPGs, the generated environments in these survival games often create space for players to fill in the gaps of the story. Because the player is not being directed down a path or along a questline, the answers to questions about the world are inferred from the players discovering elements that were randomly placed. In games like Rimworld or Dwarf Fortress, the story elements are even part of the randomly generated aspects of your world and propel the story forward as the character’s rolled traits, relationship, and personalities interact.

Those random elements are intentionally creating strange and dynamic relationships with each other to tell a random story that is compelling.

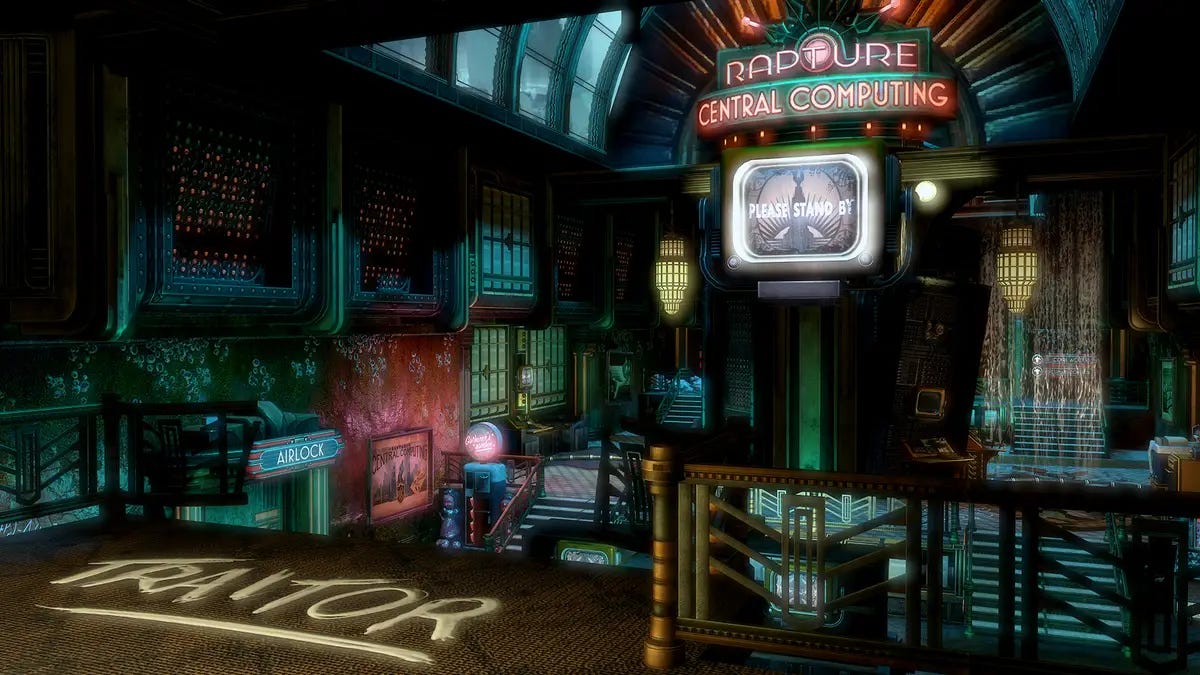

However, in a game that guides you through a particular path like the Bioshock franchise or the modern Wolfenstein reboots, or even dozens or hundreds of branching paths like some of the larger RPGs like Disco Elysium or Cyberpunk 2077, the world needs to be carefully crafted to give the intended experience.

Funnily enough, before Morrowind the Elder Scrolls games were procedurally generated, giving players MASSIVE maps to explore filled with almost nothing of note between dungeons. They actually made a much smaller map in their third game, but it was so much more interesting to explore because it was all hand-crafted.

It was all intentional.

We Happy Few struggles to give the player a consistent experience that doesn’t force them to slog through a world filled with random and often pointless filler before getting to the good stuff. It’s more like Elder Scrolls: Arena than Bioshock.

Okay, but what about good games?

We Happy Few was pretty widely recognized as having a lot of potential but being a disappointment, so let’s talk about procedural generation in some games that are critically well-received.

Remnant: From the Ashes and its sequel Remnant II have received some actual critical acclaim for their gun-toting take on the souls-like experience. Following the classic formula, you run through a variety of extensive environments from city streets to dense forests fighting an ensemble of unique and challenging enemies before getting to a boss fight that truly tests your skill.

They’re good games. I have fun playing them, with smooth combat and challenging fights. My current character has a pet dog that fights with me. I don’t want to argue that they’re bad.

I want to talk about the difference I immediately felt upon starting to play Remnant vs the origins of the genre like Dark Souls or Bloodborne: the level design. The Remnant games use procedural generation to create the paths you follow from boss to boss, which is distractingly dull compared to the compelling world you explore in FromSoftware’s games.

In Bloodborne you are navigating the cramped, winding streets of Yarnham that compel you to check every alley and sewer for cleverly hidden secrets. You are impressively steered along paths that intricately twist around themselves to tease you with sights of locations in the distance that you will eventually reach on your journey.

In Remnant you wander around a procedurally generated environment and you can feel the lack of a human touch. There are hand-crafted set pieces that are quite impressive, but the paths connecting them are thrown together by a computer to fill space and take time. Only in the points of interest do you get the scripted moments of hidden enemies jumping out to sneak attack you or cleverly designed paths you need to navigate to find a hidden room. Between them are a series of dull hallways with dead ends that can turn up empty or loop around on themselves pointlessly, filled with enemies that have no particular purpose other than slowing you down and dropping loot.

There’s no tease at upcoming sights to see or secrets that make you feel smart to discover them. Worst of all, you are compelled to explore not for the sake of seeing what the creators have in store for you, but to find the loot necessary to unlock upgrades that are randomly scattered throughout.

There’s also the added confusion of the narrative. These set piece locations often house NPCs you can talk to or journals you read to convey the story of the world you are in. However, the pacing of these locations is also randomized. My friend and I have encountered parts of the story at different times, getting wildly varied experiences and understandings of the narrative. While it would be hard to argue that the Remnant games prioritize the story, or ever really care about it much at all, it is striking how haphazard this part of the game is. There is a glaring lack of intent behind how a player encounters the fiction they are engaging with.

The Remnant games have great game play, and the set pieces in which you can feel a human touch are phenomenal, but the bulk of the world lacks the soul of an artist’s creativity. Rather than have designers handcraft levels to give curated experiences, they have forgone intent in favor of content, creating an infinitely replayable tunnel of bad guys to kill but no reason to explore it except the grind for more powerful gear to make your next tunnel of bad guys easier.

Games are replacing intent with content.

Ignoring procedural generation all together, you can even see the lack of intent surfacing in AAA titles with handmade worlds.

Take Skyrim for example. Famously boasting oodles of caves and dungeons to explore, the actual experience gets pretty stale after your first dozen or so. The ones that have story or quests associated are compelling, but of the 198 locations you can clear of enemies and loot, many are pretty samey. You get to the bottom, kill the boss room, and leave through a carefully placed tunnel at the bottom that conveniently leads you back to the start. People made these dungeons, but they are so bare-bones that they lack the soul that Bethesda’s previous titles had.

The Assassin’s Creed franchise began what I often call the “Ubisoft Game” format of adding content to a game just for the sake of content. With hundreds of collectables, repetitive quests to kill, chase, collect, find, climb the same sorts of things all over the place, there are literally hundreds of hours of stuff to do but almost none are very interesting after the first few. Climb the watchtower, clear the outpost, stop the thief. From Far Cry to Shadow of Mordor, all their games since Assassin’s Creed have been increasingly filled with these pointless tasks for the sake of content.

This tactic of repetitive quests is now seen consistently outside of Ubisoft as a company. Otherwise phenomenal games like Horizon Zero Dawn, Red Dead Redemption 2, or Cyberpunk 2077 are constantly harassing the player with copy-pasted jobs in different places around the world just for the sake of more gameplay to slog through.

We were making fun of this shit back in 2008 when your cousin Roman wouldn’t shut up about wanting to go bowling in GTA IV, and its somehow only gotten worse.

Am I just a grumbling old man?

I don’t think so. Time and time again we see that audiences prefer art that is hand-crafted by creators who are passionate about the project. People complain about “superhero fatigue” in cinema, but I think it’s really just exhaustion from Hollywood churning out soulless movies in search of easy profit. With the rise of generative AI, I worry that we will see more and more companies trying to shortcut the creative process to save costs or create “endless” content, but that will only harm entertainment media as a whole.

When designers set out with intent to create specific emotions or moments for the player in a curated experience with a definite end, it will almost always be better than a game where they set out to give you infinitely replayable content without repetition.

The latter is an impossible task without sacrificing other important aspects, often those that players fall in love with and, ironically, keep them coming back to play again and again for years to come.

Thanks for reading. I know this was a long one and if you got this far, I appreciate your interest. If you liked this, sharing it with friends or followers can help me a lot.

If you disagree, or have some examples of procedural generation being used well or poorly, let me know in the comments. This is a topic I have discussed at length and have thought a lot about, and would love to hear from you about your thoughts as well.