Games are Toys - Part 2: Components Should Matter

If the fancy pieces aren't core to the experience, they shouldn't be there.

You may have noticed this post isn’t coming out 2 weeks after my last post. Maybe you didn’t, and that’s okay. I don’t know all the schedules of the newsletters I’m subscribed to either. I realized recently that keeping to my biweekly schedule on here was getting in the way of my ability to actually design games and do the creative work I love. I was coming to dread the deadlines and wrote filler articles instead of thoughtful posts I cared about just to meet the deadlines I set for myself.

I’m moving to a loser schedule to give myself more time to work on other projects and write more about topics that matter to me. I plan on posting at least once a month, but not on any particular date.

Thanks for your continued support! Now, on with the post.

Crowdfunding has shaped how games are made.

I’ve never been a huge backer of Kickstarters. I just don’t have the spare cash available to me to support every game project I see that looks cool, and a lot of games look cool. Since much of the gaming industry is structured around crowdfunding as a pre-order system, established publishers can take less risks while games have gotten bigger and bigger, full of more and more stuff, but not necessarily better.

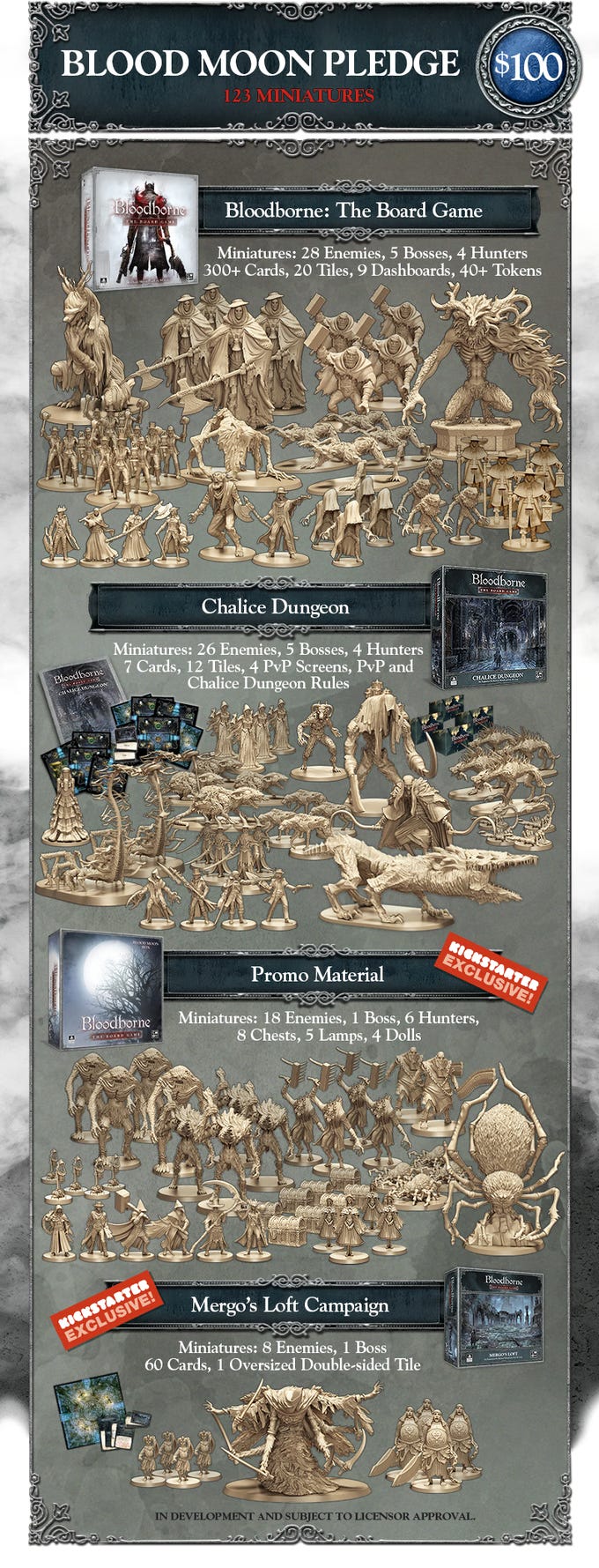

Last time I wrote, I talked about toyetic games and why I love physicality in play. Based on that, it would seem like I would be a huge fan of the miniature-heavy monstrosities coming out of the Kickstarter space. Stuff like Zombicide, Ankh: Gods of Egypt, Bloodborne: The Board Game, and plenty of other examples that don’t say CMON on the box (but they are the name that comes up a lot when people talk about this trend due to their entire catalogue comprising these types of games).

I am far from the first person to discuss the impact of crowdfunding on board games, but I wanted to write about this specifically because the avalanche of miniatures in these games technically falls into the category of toyetic games that I praised in my last post. I love these games. But the toyetic aspects of a game need to contribute to the act of play in order to be beneficial to the experience, and in many cases these Kickstarter boxes of luxury plastic do not. Instead, they price out potential players by including superfluous components rather than focusing on the core experience.

Cool minis, or maybe not.

Massive blowout successes on Kickstarter in the last decade have caused a trend of many board games becoming unwieldy piles of boxes filled with plastic miniatures that largely add nothing to the actual gameplay, and CMON is by far the biggest offender. It’s not necessarily bad or wrong of them, and it has been the identity of their company since they were still called “Cool Mini Or Not.” But it prices many players out of the base experience that would otherwise be far more accessible.

It’s a really successful marketing tactic. These games look awesome because they’re full of super cool STUFF. They have great table presence, gorgeous art, incredible sculpts, and tons of exclusive “content” you can’t get after the campaign. With the power of FOMO, they get lots of backers and exceed funding goals by massive margins. Using the crowdfunding campaign as a pre-order system, they won’t over print copies and can ensure they sell every box that’s produced.

It’s smart business.

Because crowdfunding platforms are inescapable in the hobby game industry, the success of this model is an incentive that has created a market flooded with massively overpriced luxury games with tons of plastic models that could easily have been cardboard standees without fundamentally changing the game.

Imagine if Dead of Winter were made today via crowdfunding. It would be on Kickstarter or Gamefound and have 40+ minis for $90, or you could get the Frostbite Edition that comes with an extra pack of new characters and 20 more minis for $130, or you could add another Kickstarter Exclusive expansion at release for… well, you get the idea.

That game, and so many of these titles, function perfectly well without the miniatures that come in the box. Cardboard tokens, meeples, or any other number of game pieces could be used to represent the same things that are instead expensive plastic models. The prices usually start at around $100 or more for a midweight game that could be a $50-60 game if it weren’t packed with extraneous components for the sake of marketing.

Don’t get me wrong. Just because a game has 1.609e+6 minis in 63346 stretch goals packed into 527 boxes, it isn’t necessarily a bad game. There are plenty of examples of really good games from CMON and other companies making these monstrosities. Ankh: Gods of Egypt was received well by No Pun Included. The Bloodbourne Board Game has a 7.8 on Board Game Geek which, despite being less than the total number of boxes shipped for the highest pledge available, isn’t a bad score. The debate about the effect crowdfunding has on quality of games is valid but isn’t what I am getting at here.

I’ll admit these things look cool. The components feel hefty and it’s fun to move big hunks of plastic around a board. The monsters tower over the little player pawns, which can be super cinematic. It’s succeeding at creating that vibe.

And while the minis technically meet the requirements for “toyetic” that I established in my previous post, the toy-like components aren’t really used as a core feature of gameplay. Unlike Barrel of Monkeys, the toyetics aren’t a unique component you engage with through mechanics, they are a figure on a board that looks really cool to represent a character or item in the game and doesn’t do much else.

They might as well just be figures to display on a shelf.

These companies are more like Games Workshop, a miniature company selling impressive art pieces that happen to be used in a game. The game itself doesn’t need the fancy plastic in order to function.

Expensive plastic.

I didn’t discuss miniature war games in my last post about toyetic games. This was purposeful, because I think they fit into the spectrum strangely. The aspect of assembling and painting armies is its own fundamental part of play in those hobbies.

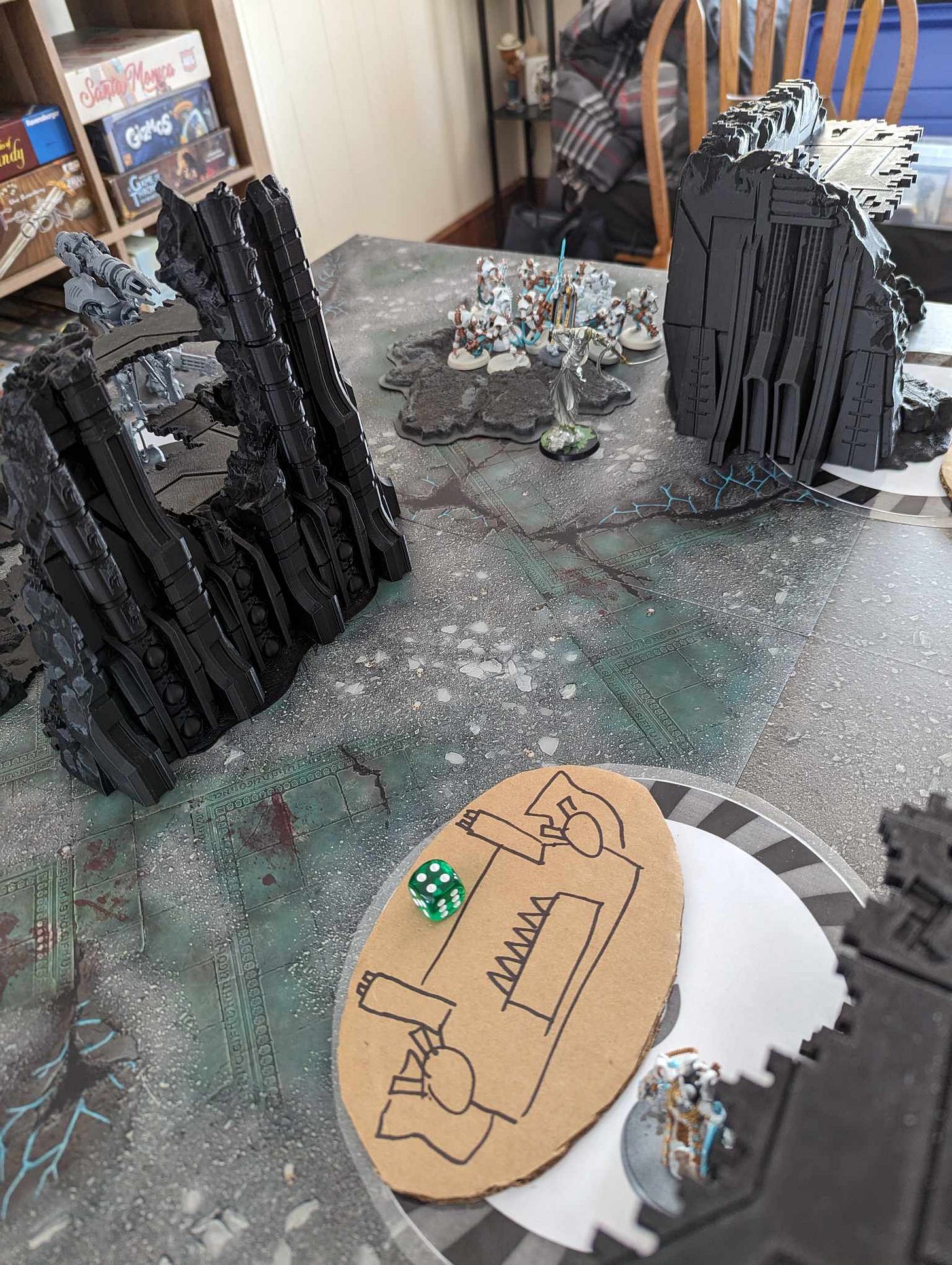

For example, let’s use Warhammer. The game itself could be played with cardboard, and some players lovingly call the game “poorhammer” when not investing in the pricey Games Workshop plastic. Playing a game of Warhammer 40k doesn’t require $300 worth of miniatures. The rules are available online and you can cut out cardboard templates for the correct base sizes. I’ve done this myself to test out armies or mechanics to see if I enjoyed the game.

The act of play doesn’t start and stop when the minis are on the table. Assembling models is tactile and engaging. Painting them to match a color scheme you chose is self-expression and creative. The hobby-side of miniature war games is a part of the play, so I don’t really think it falls into the same category as CMON board games. While you can paint the models that come in the games, it isn’t the focus. It isn’t why you buy the box.

Components should matter.

If a game includes a cool splashy component, or dozens, I want to play with it. I want it to physically matter. The way it’s shaped, the way it moves, and the way I interact with it should have an impact on the gameplay.

Everdell, a perfectly good board game with a solid 8 on BGG, has this very pretty tree that stands on the board and holds some cards and other components. It grabs attention, looks really cool, and doesn’t actually matter at all. The game could play exactly the same if the cards were on a flat board on the table.

Staying in theme, Photosynthesis also has some trees on the board. They look cool, grab attention, and are the core components used to play the game. In Photosynthesis, you score points when the sun is shining on your trees. Taller trees tower over the shorter trees, getting sun even when the smaller ones are in the way and blocking the sun on shorter trees across more spaces. This makes sense in the fiction of the game and is visually conveyed by the components themselves. As your trees grow, you replace the tree token with the next size up, both a beautiful presentation and a physical representation that brilliantly communicates vital information about the mechanics of the game to all the players at a glance.

This juxtopasition gets to my larger point.

If a game is toyetic, with tactile components and mechanics that involve physical manipulation of game pieces, then those components have a reason to be more than simple tokens. If they serve no significant purpose, keep the luxury plastic in a deluxe edition or upgrade packs. Let those who want to pay for a premium experience buy your add-ons, and let those of us who want to play your game afford to do so.

Are there any egregious examples I missed, or am I off the mark in some way? As always, let me know what you think in the comments.

Share this with people who you think might enjoy it and subscribe for upcoming posts.

Thanks for reading!